Marketing Is a Math Problem

How I went from dismissing marketing to discovering the order of operations behind it.

If you think marketing is fluffy, I don’t blame you. I used to think the same thing.

To me, marketing never felt like a real discipline. In college, I mentally grouped it with art history and photography. Nice, creative, subjective.

It was nothing like physics, chemistry, or math (the subjects I loved because they were precise). You had formulas, rules, and the right answer. Marketing felt like something creative types invented because they didn’t like structure.

Too vague, too loose, and too dependent on “taste.”

I avoided marketing everywhere I could. I don’t even remember how I passed the one marketing class I took in undergrad, and in business school I didn’t waste a single credit on it. I genuinely didn’t see the point.

I wasn’t supposed to be a marketer. I was a Strategy and Operations lead. But I was obsessed with Product-led Growth (PLG): engineering in-product tests to reduce friction and maximize adoption. I wanted to turn the product itself into the main engine of expansion.

I was so desperate to explore that opportunity that I was willing to take any path to get there, including stepping in to lead a Product Marketing team.

The Opinion Trap

I’ll admit it: before stepping into this role, I was a total know-it-all when giving feedback to marketers (if my old team is reading this… please forgive me).

You’ve probably seen a version of that with everyone arguing over the words without agreeing on what the product value actually is. Then there are alignment meetings with opinions fighting opinions. The loudest voice, the most convincing slide deck, or the highest-paid person opinion usually wins.

But when I took the role and had to work with a team of actual marketers, it hit me really hard. Sure, with my experience in product, my knowledge of the customer base and market insights, and, okay, maybe even some decent taste, I knew enough to sound competent, but not enough to teach or lead marketers. That gap terrified me.

I needed a framework. I needed something I could use myself and introduce to the team so they knew exactly how to achieve excellence without relying on intuition.

We were promoting financial products to busy business owners who avoided the topic of “finance”. They’d hand you off to their accountant, their admin, their spouse, really anyone but themselves. Meanwhile, the product team kept shipping faster. Features multiplied tenfold.

Attention stretched thin. Product managers reached out to customers to do product discovery. Sales reps kept calling trying to upsell. Customer success team was pushing adoption. Everyone needed something from the same people, and those people were already overwhelmed.

In that environment, strategy, analysis, and research were treated like dirty words. Any mention of them sounded like a delay. You might’ve seen this yourself where anything that sounds too slow or too thoughtful gets dismissed as “theoretical.”

But the truth is I had enough familiarity with products, customers and competition that I could wing it, but if I were to lead and scale the team, I couldn’t succeed without structure. I was spending nights, weekends, and early mornings trying to build frameworks I could share with more employees and make it easy to understand what they needed to do in order to move business outcomes and grow their careers.

I dove into analysis like an open-ocean explorer with no stone left unturned. But every time I thought I had figured something out, one skeptical executive would tear it down. The feedback felt like a bucket of ice water thrown at me. And before I could catch my breath, another marketing initiative would land on my plate… with another full GTM plan due in 48 hours.

I was told I was too analytical, too slow, too structured. That I needed to “just do it” instead of thinking it through. And honestly, it often felt like impulsive action would’ve been rewarded more than thoughtful planning. The pressure kept building. The friction kept mounting. I was exhausted and out of alignment with how I naturally operate.

And the truth, which I can only articulate now, is this: I was trying to create a system for something I didn’t yet understand. And the harder I pushed, the more friction I saw.

So, I did what any analytical person does when faced with ambiguity: I read a few books, studied many experts, and I engineered my own product positioning framework. And then I tried to get everyone to adopt it. For months. If you’ve ever tried to force rigor onto something you secretly suspect is subjective, you know exactly how it feels. It was a total failure.

My interpretation was wrong. The process I built was so analytical, so rigid, and so time-consuming that you could practically feel the sharp edges of it. People followed it because I insisted, not because it helped.

I didn’t just deliver a weak framework, I dragged an entire team through months of unnecessary work.

I still remember sitting in front of my laptop after an exec shredded my beautifully structured but fundamentally wrong framework in under a minute. I felt the air leave my lungs. It wasn’t the critique, it was the realization that he was right.

I didn’t think it could get any worse.

But here’s the interesting thing: even then, I couldn’t let it go. I’ve always had that slightly obsessive, slightly nerdy drive to push on a problem until something cracks. And eventually, something did.

I stumbled onto one more product marketing course, almost by accident. You know that feeling when you’re not expecting anything useful, but you’re desperate enough to click anyway? That was me. And it forced a breakthrough insight.

The problem wasn’t that marketing lacked structure and that my framework was completely wrong. It was that I had been using structure in the wrong order. And once you see that the problem isn’t the existence of structure but the sequence in which you apply it, everything changes.

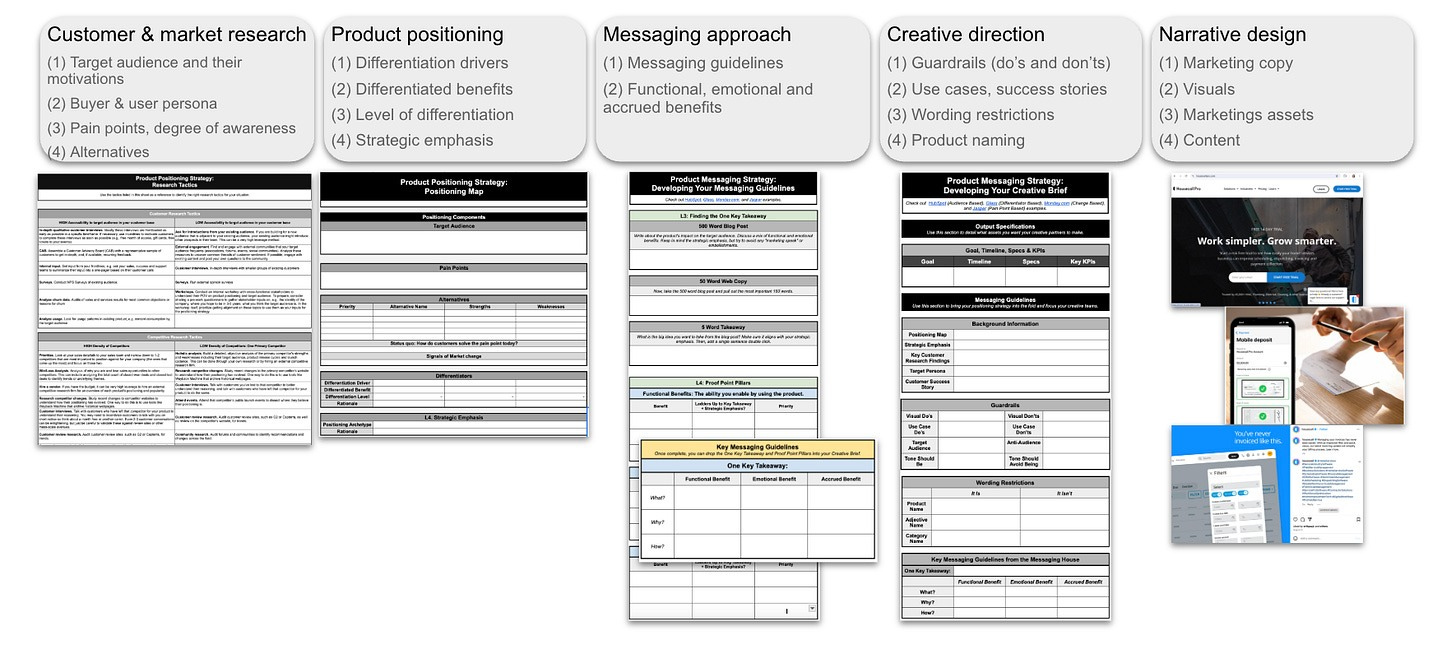

There is a precise Order of Operations that governs how products get positioned, messaged, and taken to market.

If you violate the sequence, everything breaks.

I went back to the work. Once I applied the right sequence, our PLG tests started showing conversion lifts of 50%. Then more. It finally felt like I was moving in the right direction. The tests were proof that marketing has a deterministic formula that anyone can use.

Seeing the Matrix

Here’s the irony.

After all those years thinking marketing was the “soft” side of business, the discipline where opinions win and nothing is predictable, I now see the formula everywhere.

It’s almost embarrassing how obvious it is now. It’s like driving with your headlights on for the first time and wondering how you ever navigated in the dark.

Now, when I speak to leaders across industries struggling with GTM, whether they are reinventing after ChatGPT disrupted their market or trying to align sales on a new buyer persona, I recognize the pattern instantly.

I can pinpoint the exact variable that is misaligned in their sequence.

Marketing isn’t about intuition or taste. It’s about the right input in the formula.

Stop looking for taste. Start using the equation.

Very close to home!